Why Segregation of Duties is Essential

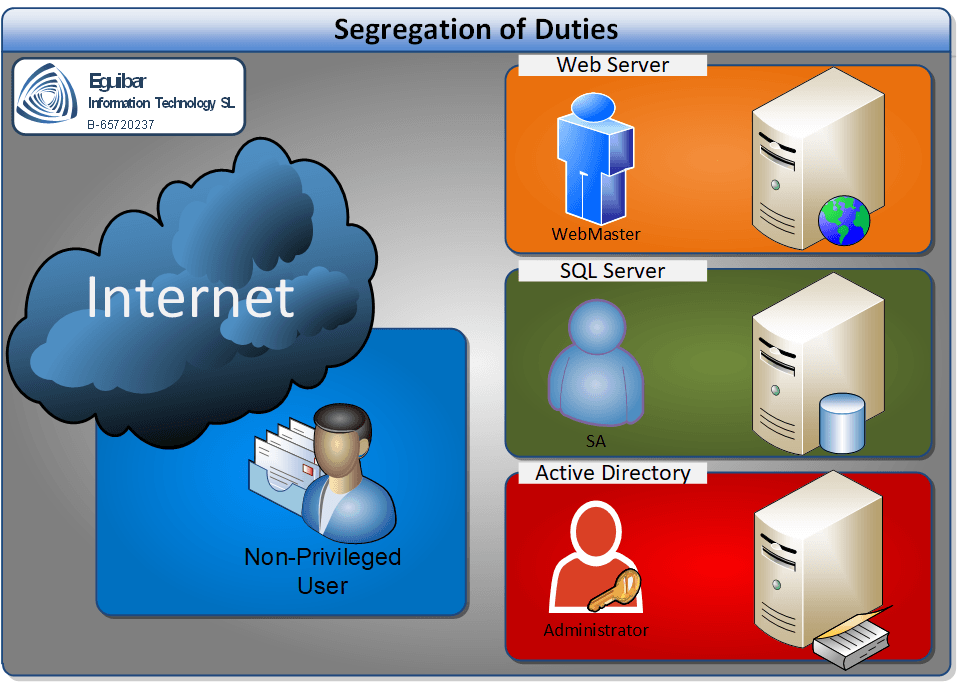

In most organizations, a single privileged account can access dozens of systems, databases, and critical infrastructure. If that account is compromised, an attacker gains access to all of them simultaneously. Segregation of Duties (SoD) is the practice of dividing administrative responsibilities so that no single account has unrestricted power across all systems. Instead, each administrator holds separate accounts for specific domains: one for file servers, another for databases, another for Active Directory, and so on.

SoD is not a new concept. Financial institutions have long practiced it: the person who approves a payment is not the same person who executes it. The same principle applies to IT administration. If one account can approve a security group change, provision a user, and install privileged software, then a compromise of that account is catastrophic. But if three different accounts are required—one to approve, one to provision, one to deploy—then the attacker must compromise all three to succeed.

The challenge is balancing security with operational complexity. More segregation means more accounts, more passwords, more audit logging. Too little segregation leaves the organization vulnerable to lateral movement and privilege escalation. This article shows how to design a SoD model that is both secure and operationally sustainable.

Core principles of Segregation of Duties

Effective SoD rests on three foundational principles: least privilege, role separation, and asset compartmentalization.

Least Privilege: Every administrator should hold the minimum permissions necessary to perform their role. If a help desk technician needs to reset passwords in one organizational unit (OU), they should not hold Domain Admin or even global delegated permissions. Instead, they should receive a semi-privileged account scoped only to that OU with only the "Reset Password" permission. This limits both what they can do intentionally and what an attacker can do if their credentials are stolen.

Role Separation: Administrative domains should be strictly separated. A file server administrator should not hold database admin permissions. A DNS administrator should not hold Active Directory schema permissions. Each role gets its own account, group membership, and audit trail. If a file server admin's account is compromised, the attacker can modify file shares but cannot create users in Active Directory or modify the database.

Asset Compartmentalization: Physical and logical assets should be grouped by risk and function, with separate privileged accounts for each compartment. For example, in a 500-computer environment, if all machines share the same local administrator password, a compromise of one machine exposes all 500. Instead, each machine (or group of machines by function) should have a unique local admin password. If Machine A is compromised, Machines B-Z remain protected because the attacker cannot use Machine A's credentials elsewhere.

Common Pitfall: Admins often create segregation on paper ("we have different accounts for different roles") but reuse passwords across roles or grant accounts more permissions than their documented function requires. SoD is only effective if the actual permissions match the documented role and are audited regularly.

Implementation strategy

Implementing SoD is a multi-phase process that requires discovery, design, and careful rollout.

Phase 1: Discovery and Risk Assessment. Audit your current environment to identify all administrative accounts and their permissions. Query Active Directory for all members of Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins, Schema Admins, and custom admin groups. Interview operational teams about their actual day-to-day tasks. Ask: Who manages file servers? Who manages databases? Who manages DNS? Who manages Active Directory? For each role, document what systems they touch and what operations they perform. Simultaneously, assess the risk landscape: Which systems are most critical? Which would cause the most damage if compromised? Which data is most sensitive? This assessment will inform your segregation priorities.

Phase 2: Design Segregation Model. Based on your discovery, define segregation boundaries. Start with the three broadest categories: non-privileged users (standard employees), semi-privileged users (delegated admins like help desk), and privileged users (domain admins). Then subdivide privileged users by domain: file admins, database admins, directory admins, network admins, and so on. For each role, define its scope (which systems does it touch?), operations (what can it do?), and guardrails (what is forbidden?). Create naming conventions for accounts and groups (e.g., sg-ADmins-FileServers-All, sg-ADmins-DNS-Zone1). Document everything in a central registry.

Phase 3: Testing and Pilot. Before enforcing segregation organization-wide, pilot it with a subset of systems or teams. For example, grant new segregated file server admin accounts permissions only to a test file server for 30 days. Monitor logs for permission failures (may indicate gaps) and collect feedback from admins. Adjust permissions and processes as needed. Once the pilot succeeds, gradually roll out to production systems. For sensitive systems (like Active Directory), use a phased approach: first shift read-only functions to non-admin accounts, then shift routine operations to semi-privileged accounts, and finally restrict Domain Admin access to emergency-only scenarios.

Phase 4: Validation and Ongoing Audit. After deploying segregation, audit that it is actually in place and effective. Quarterly, re-run your discovery scripts to verify that account permissions match the documented model. Check for permission drift (accounts that accumulated more permissions than their role should have). Identify unused or orphaned accounts and remove them. Use Activity Alerts on critical groups (e.g., Domain Admins) to detect unexpected membership changes. Build this audit into your operational calendar as a recurring task.

Real-world examples of Segregation of Duties

File Server Administration: A team of storage admins manages shared file servers across the organization. Instead of holding Domain Admin credentials, they each have a dedicated semi-privileged account (e.g., jsmith_FileAdmin) granted permissions only to modify share permissions, group memberships for share access, and quotas on the file servers. The account cannot modify Active Directory, cannot touch database servers, and cannot change domain policies. All file share changes are logged and reviewed weekly. If this account is compromised, the attacker can modify file shares but cannot escalate to domain-wide access.

Database Administration: Database admins have a separate account (e.g., jsmith_DBAdmin) with permissions to create/modify databases, users, roles, and backups. This account is not a member of Domain Admins and has no rights to file servers or directory services. It is MFA-protected and rotates passwords every 90 days. Database activity is logged to a SIEM with alerts for unusual queries or privilege grants. Because this account cannot touch Active Directory, a compromise cannot spread to user provisioning or group management.

Active Directory Administration: Only one or two senior architects hold Domain Admin accounts, and these are used only for emergency scenarios or major forest changes. Day-to-day AD administration (creating users, resetting passwords, managing groups) is delegated to semi-privileged accounts scoped by OU and permission. For example, a regional IT manager has an account with permissions only to create/modify users within their regional OU, add them to regional groups, and reset passwords within that scope. This account cannot touch tier-0 accounts, cannot modify group policies, and cannot change Active Directory structure.

Local Administrator Passwords: In a 500-computer environment, each machine (or logical group of machines by function) has a unique local administrator password, stored in a password vault (e.g., Microsoft LAPS, HashiCorp Vault, or similar). When an admin needs local access to a machine, they request it from the vault (which logs the request and grants temporary access). If one machine's local admin password is compromised, the vault prevents it from being used on other machines. This containment is critical for limiting lateral movement.

Key Pattern: Each segregated account is bounded by scope (OU, system, database), permission (specific operation), and auditability (logged and reviewed). No account is used for multiple purposes. The principle is: one account per role, one role per account.

Monitoring and validation

SoD is only effective if you actively monitor that segregation is maintained and catch violations early.

Audit Logging: Enable detailed audit logging on all administrative actions. In Active Directory, enable Advanced Audit Policy: Directory Service Changes (event 5136 for object modifications), Group Membership (events 4728, 4729, 4730), and Account Management (events 4722, 4724, 4726). On file servers, enable auditing of share permission changes. On database servers, log all privilege grants and schema changes. Forward all logs to a central SIEM with real-time alerting.

Anomaly Detection: Set up alerts for violations of your segregation model:

- Unexpected group membership (e.g., file admin account added to Domain Admins).

- Cross-scope access (e.g., file admin account accessing database servers).

- After-hours usage (if admin accounts should only be used during business hours).

- Permission escalation (e.g., account requesting higher privileges than its role allows).

Quarterly Access Reviews: Every quarter, audit the roster of admin accounts and verify:

- Each account is still assigned to an active employee.

- Each account's permissions match its documented role (no permission drift).

- Unused or orphaned accounts are removed immediately.

- Shared accounts (if any exist) are disabled or have restricted, logged access.

Incident Response for SoD Breaches: If an admin account is compromised, immediately isolate it. Disable the account, reset its password, and revoke all group memberships. Audit all actions performed by that account since the compromise was discovered. If the account held sensitive permissions (Domain Admin, database admin, etc.), assume that systems it had access to are potentially compromised and run forensic checks. Notify security and affected stakeholders. After remediation, conduct a post-incident review: How was the account compromised? What could have prevented it? Does the segregation model need adjustment?

Benefits and risk mitigation

Defense Against Lateral Movement: SoD creates natural barriers to lateral movement. If an attacker compromises a non-privileged user account, they cannot immediately escalate to file servers or databases because those systems are administrated by different, segregated accounts. The attacker must find and compromise each segregated account separately, which takes time and leaves more audit trails. Each breach-and-compromise cycle gives your security team more opportunity to detect and respond.

Containment and Damage Limitation: If a segregated account is compromised, the attacker's access is limited to that account's scope. If a file admin account is compromised, the attacker can modify file shares but cannot touch Active Directory, databases, or domain policies. If a database admin account is compromised, the attacker can access the database but cannot create domain users or provision servers. This compartmentalization turns a single breach into a localized incident rather than a forest-wide compromise.

Improved Audit Trails and Accountability: Each segregated account has its own audit logs. When a security group is modified, the logs show exactly which admin account performed it. When a file share permission changes, the logs show which file admin made the change. This accountability discourages insider misuse and makes forensic investigation faster. If an unauthorized change occurs, you can immediately identify who made it and ask why.

Enabler for Least Privilege: SoD supports the broader least-privilege principle. By segregating roles, you can grant each account only the minimum permissions for its function. A help desk technician gets an account that can reset passwords in one OU, nothing more. An application team gets an account with permissions only to their application's servers. This minimization reduces the attack surface and makes compromise less catastrophic.

Realistic Limitations: SoD is powerful but not a silver bullet. If your directory (Active Directory, LDAP, etc.) is compromised, an attacker may be able to modify or delete segregation controls themselves. If an attacker gains physical access to a domain controller, they can bypass many SoD measures. If admins share passwords or leave credentials written down, SoD controls are circumvented. SoD works best as part of a multi-layered defense that includes strong authentication (MFA), privileged access management (PAM) tools, network segmentation, and continuous monitoring.

Related guidance

Segregation of Duties is foundational to several related security practices. To build a complete access control architecture, also review:

- Least Privileged Access — Strategic framework for minimizing standing privileges across your entire environment.

- Privileged and Semi-Privileged Users — How to define and operationalize segregated admin roles.

- Tier Model — How to segregate systems and accounts by trust level and criticality.

- Delegation Model — How to implement delegated administration roles in Active Directory.

- 0-Admin Model — A specialized architecture with minimal standing privileges for tier-0.

- Enterprise Access Model — End-to-end access control design for large, multi-tier environments.