Table of Contents

Why 7 If We Can Do It With 3?

Imagine a scenario: you need administrative access to a new environment, so you receive Domain Admin rights. On the surface, this seems practical—you can do whatever you need. But consider the security implications: you now have complete control over every system, every user, every group, and every policy in that entire domain. That's exponentially more power than you likely need for your specific tasks.

This is the paradox of permission assignment: it's easier to grant broad admin rights than to carefully scope specific permissions. But this convenience comes at a massive security cost.

The Default Problem

Many organizations default to broad permission grants not from malice, but from operational convenience and habit. "Domain Admin is easier than figuring out exactly what they need." This mindset, repeated across the organization, creates an attack surface that's orders of magnitude larger than necessary.

The Principle & Foundation

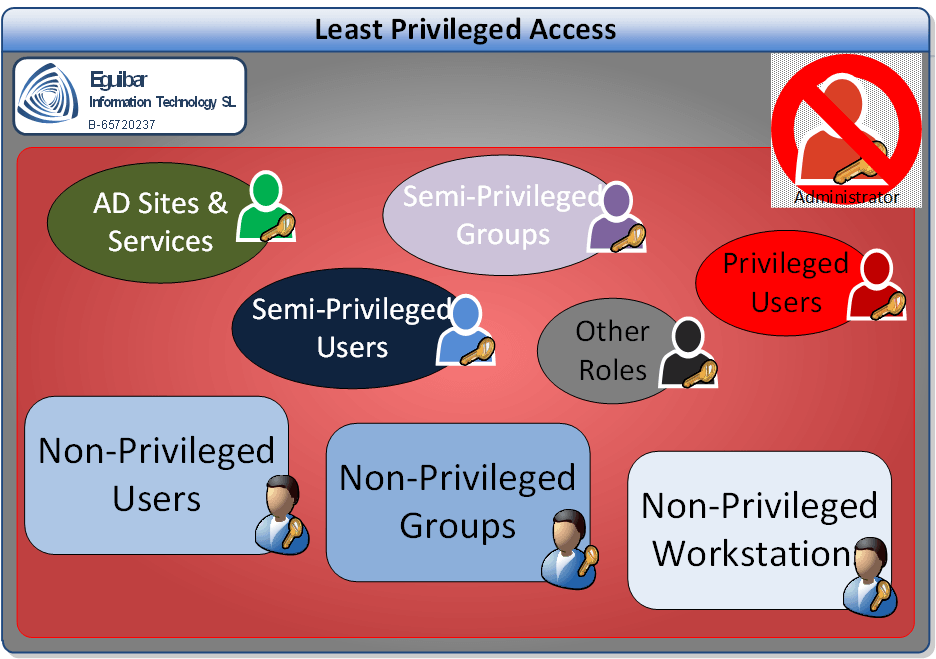

The principle of least privilege (PoLP) is a foundational security concept: users should have only the minimum levels of access—or permissions—needed to perform their job functions. This approach helps to reduce the attack surface and limit potential damage in the event of a security breach.

At its core, least privileged access means: have nothing more than the permissions you need to complete your task, nothing less.

The LPA Mindset

Least Privileged Access is not about distrust—it's about resilience. You trust your administrators, contractors, and staff. But trusting people doesn't mean giving them unlimited power. It means designing systems where mistakes or compromises have limited impact, and where accountability is clear.

We have to understand that the built-in groups, like Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins and Administrators, have all the rights and privileges to do anything we need in the environment.

Built-in admin groups exist for a reason: initial setup and very limited tasks that cannot reasonably be delegated. When you first deploy a Domain Controller, the Administrator account has all rights required for foundational configuration. But once setup is complete, this account should be locked away—used only for emergency break-glass situations or rare infrastructure events.

The key insight: most day-to-day administrative work does not require full domain admin rights. User provisioning doesn't need domain admin. Group management doesn't need domain admin. Password resets don't need domain admin. Yet many organizations keep administrators in these groups permanently, 24/7, carrying that unlimited power for routine work.

Understanding Built-In Groups

Before you can implement least privilege, you must understand what built-in groups actually do. This is critical because many assumptions are wrong:

Domain Admins

Members can manage the entire domain, create/modify policies, manage domain-wide security. Legitimate use: rare infrastructure tasks. NOT needed for: user management, group management, password resets, routine changes.

Enterprise Admins

Members can manage forest-wide changes, promote domain controllers to new domains. Legitimate use: forest-level infrastructure changes (2-3 per year max). NOT needed for: almost everything else in day-to-day operations.

Administrators (Built-In Group)

Members have full control over the local machine or domain. On domain controllers, this group is extremely powerful. Legitimate use: server administration. NOT needed for: delegated AD management tasks.

Account Operators

A middle-ground group that can manage users and groups—but here's the problem: it manages ALL users and groups by default, including semi-privileged accounts. This violates segregation of duties. If you want to use this model, you need constraints (e.g., PowerShell filtering) to prevent managing privileged accounts.

The Account Operators Trap

Many organizations use Account Operators as a middle-ground between "no access" and "full admin." The problem: this group can modify both standard users AND semi-privileged accounts by default, violating segregation of duties. If you use Account Operators, implement scope limitations and alternative delegation models.

Building Your LPA Strategy

Implementing least privilege is not a one-time project—it's a strategic design process. Here's a conceptual framework:

1. Understand Your Environment & Tasks

First step: Map every administrative task executed in your domain. Map every administrative task executed in your domain:

- User lifecycle management (create, modify, disable, delete, reset password)

- Group management and membership changes

- Computer/workstation management

- Organizational Unit creation and policy management

- Exchange/mail system delegation

- File share and resource delegation

- Security policy and compliance updates

- Password policy and account lockout management

For each task, identify: Who does it? How often? What permissions are actually needed to complete it?

2. Identify Your Roles & Personas

Second step: Define the different administrative personas in your organization:

- Infrastructure/DC Admins: Domain controller provisioning, OS patching, backup/restore

- User/Identity Admins: User provisioning, lifecycle, password management

- Resource/Group Admins: Group management, shared resource delegation

- Help Desk/Support Staff: Password resets, account unlocking, basic troubleshooting

- Audit/Compliance: Read-only access to audit logs and security events

- Application Teams: Delegation for their app-specific resources (Exchange, SharePoint, etc.)

Your organization might have different roles or subdivisions, but the principle remains: be specific about who needs to do what.

3. Design Role-Based Permissions

Third step: For each role, define the minimum permissions needed:

- Scope: Which OUs or objects can they modify?

- Operations: Which specific actions can they perform?

- Exclusions: What should they explicitly NOT be able to do?

- Frequency: How often do they need this access? (constant, as-needed, temporary)

4. Assess Current State

Audit your existing environment to understand current privilege grants:

- Who is in Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins, Administrators groups?

- Who has "full control" delegations on OUs or groups?

- Which service accounts have excessive permissions?

- What delegations already exist? Are they properly scoped?

- Which roles overlap or conflict with each other?

5. Create Delegation Model

Key point: Move from assessment to action: create specific groups and delegate minimal permissions (e.g., a User_Managers group scoped to Sales OU, department-specific group managers, or a PasswordReset_Tier1 group limited to standard user OUs).

LPA Implementation Mindset

Move from asking "What can I give this person?" to asking "What is the minimum this person needs, and who else shouldn't have that permission?" This inversion of thinking is the foundation of least privilege.

Real-World Role Examples

Understanding abstract principles is important, but seeing them in practice makes them concrete. Here are conceptual role examples showing how LPA applies in real organizations:

User Lifecycle Manager Role

Responsibility: Create, modify, and decommission user accounts for specific departments.

LPA Approach: Instead of Domain Admin, give rights to create/delete users in the Finance OU, modify user properties, reset passwords and unlock accounts for Finance, and move users within Finance OUs. Not allowed: group membership changes, creating admin users, touching other departments’ OUs, policy changes, or DC promotion.

Help Desk / Tier 1 Support Role

Responsibility: Reset passwords and unlock accounts for end users.

LPA Approach: Allow password resets and unlocks in standard user OUs (explicitly excluding privileged/semi-privileged OUs) and read-only view of user properties. Not allowed: create/delete users, change other properties, access resource groups, or see sensitive attributes.

Group & Resource Manager Role

Responsibility: Create and manage security groups and distribution lists for their department, control group membership.

LPA Approach: Delegate group creation/deletion inside their OU, membership changes for non-privileged groups, and basic property edits (description, email, owner). Constraint: Filters block any group containing “Admin,” “Privileged,” or “Security.”

Infrastructure / DC Admin Role

Responsibility: Domain controller maintenance, OS patching, backup/restore, rare domain-wide changes.

LPA Approach: Even here, avoid permanent Domain Admin. Do routine work with scoped rights; use Just-In-Time elevation for rare infrastructure changes with automatic timeout, full audit logging, and required justification; keep break-glass credentials only for disasters.

Audit / Compliance Role

Responsibility: Review AD changes, verify access controls, generate compliance reports.

LPA Approach: Give broad read-only visibility (objects, properties, audit/security logs, membership reports) with zero modify rights.

The JIT Principle for High-Risk Access

Even infrastructure admins shouldn't be permanent Domain Admins. Instead, implement Just-In-Time access: users request temporary elevated rights for specific tasks, receive them with automatic timeout, and all actions are audited. This preserves capability for rare high-privilege work while dramatically reducing the attack surface for everyday operations.

What We Can Achieve With LPA

The benefits of implementing least privilege extend far beyond simple security metrics:

Reduced Attack Surface

By granting the minimum amount of privileges and rights, we reduce the attack surface of our domain. An attacker who compromises a Help Desk account can reset passwords—period. They cannot create privileged users, modify group policies, or access sensitive OUs. Each compromised account limits the damage to that account's specific permissions.

Reduced Insider Threat Risk

We reduce the risk of intentional misuse of privileges. If an employee becomes disgruntled or is about to leave, their limited permissions mean limited damage. Additionally, segregated duties make fraud harder—no single person has enough permissions to commit sophisticated attacks alone.

Reduced Accidental Damage

We reduce the risk of accidental or unintended misuse of privileges. An admin with full domain control might accidentally delete a critical OU or modify the wrong policy. With scoped permissions, mistakes are automatically bounded—they can only affect the resources they have access to.

Lower Privilege Escalation Risk

We reduce the risk of privilege escalation attacks. If most staff have narrow, scoped permissions, an attacker has fewer stepping stones to reach full domain control. Each escalation requires breaching additional role separations.

Enhanced Audit & Accountability

Instead of a domain-wide audit log showing "Domain Admin changed something," you see precise role-based actions: "User_Manager_123 created user account in Finance OU." This clarity is essential for:

- Incident investigation—knowing exactly who had the ability to make specific changes

- Regulatory compliance—SOC 2, ISO 27001, HIPAA, and others require clear accountability

- Forensics—understanding who made controversial or suspicious changes

Improved Compliance Posture

We improve compliance with regulatory requirements. Most security frameworks (NIST, CIS Controls, SOC 2) mandate least privilege as a core control. Organizations implementing LPA have a clear, documented answer to audit questions about access control and segregation of duties.

Organizational Clarity

We have a clear overview of who is doing what, instead of relying on general-purpose built-in groups and assuming people stay within appropriate boundaries. With LPA, the system enforces boundaries. Documentation of roles and permissions becomes a living record of your access control architecture.

Operational Resilience

Organizations with mature LPA models are more resilient to security incidents. When a breach occurs, it's contained to the specific permissions that account held. Recovery is faster and damage is limited. Compare this to an organization where half the staff are Domain Admins—a single compromised account can mean full domain compromise.

LPA as a Strategic Advantage

Organizations that implement LPA don't just become more secure—they become more operationally mature. They understand their systems better, can respond to incidents faster, and have the documentation and structures in place for compliance, auditing, and incident response. LPA is a mark of security sophistication.

Challenges & Organizational Considerations

Implementing least privilege is conceptually straightforward but organizationally complex. Here are the key challenges:

Upfront Effort & Knowledge Requirements

Building an LPA model requires detailed knowledge of your environment, tasks, and permission structures: map all administrative tasks (often more than leadership realizes), understand AD delegation, design role definitions and scopes, and test thoroughly so nothing breaks.

For most mid-sized organizations, this is 2-4 months of focused work.

Organizational Change Management

Staff accustomed to having broad admin access often resist restrictions, even when justified:

- "I might need it" → Requires a JIT or escalation process they trust

- "This is inconvenient" → Balanced against security benefits and compliance requirements

- "You don't trust us" → Frame as system design, not personal trust

Executive sponsorship and clear communication of security benefits are essential.

Documentation & Governance

An LPA model must be documented and maintained: catalog roles, their permissions, members, and how requests for new roles or changes are handled. Without governance, "just one more thing" requests cause permission creep.

System & Tool Alignment

Your infrastructure must support LPA:

- Can AD delegation express the fine-grained permissions you need?

- Do your management tools (AD Users & Computers, PowerShell, third-party tools) work well with delegated permissions?

- Do your ticketing/approval systems support role-based access requests?

- Can your SIEM/audit tools track delegated permissions separately from admin permissions?

LPA is Not a One-Time Project

Implementing LPA is not a checkbox item—it's an ongoing practice. As your organization evolves, roles change, staff turnover occurs, and new systems are added. You need continuous governance and periodic reviews to keep your LPA model effective.

Further Reading & Resources

To deepen your understanding of least privilege and related security concepts, explore these resources:

Internal resources: Delegation Model, 0 (Zero) Admin Model, Segregation of Duties, Privileged & Semi-Privileged Users, Enterprise Access Model, and Privileged Access Workstations.

Related concepts: Tier Model, Active Directory Fundamentals, and AD Security Q&A.

External resources: Microsoft Learn: AD Security Best Practices; CIS Controls 5 & 6; NIST CSF PR.AC; SANS "Implementing the Principle of Least Privilege."