Why clarity matters: privileged, semi-privileged, and non-privileged roles

One of the most persistent sources of confusion in Active Directory governance is terminology. Across organizations, regions, and vendors, the same concepts go by different names. Is that account a "domain admin," an "operator," a "delegated admin," or something else? Without shared vocabulary, teams talk past each other, security decisions become inconsistent, and audit trails become cryptic.

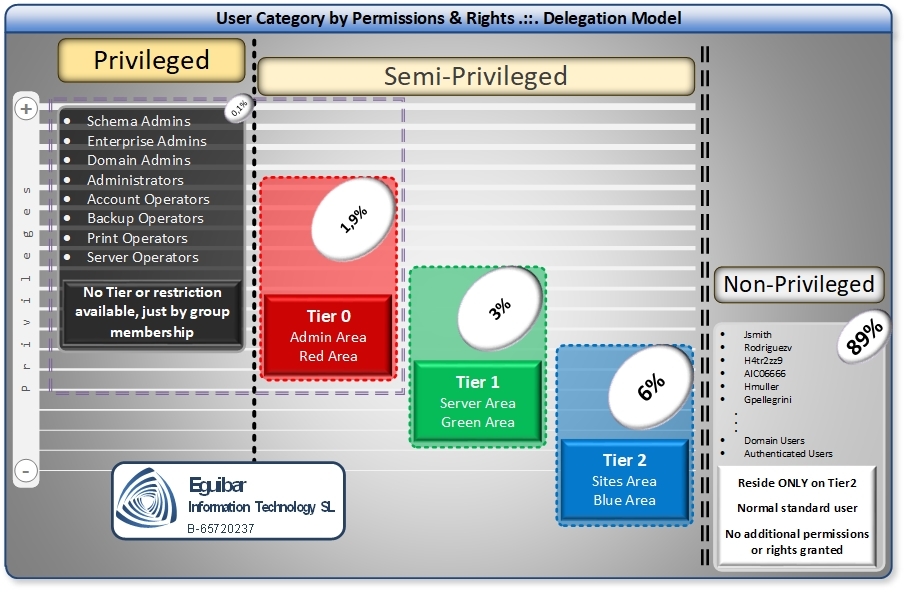

This article establishes clear definitions: Privileged users hold unrestricted administrative power (domain admin, forest admin). Non-privileged users are everyday workers with minimal permissions. Semi-privileged users occupy the middle ground: they hold elevated permissions bounded by function, allowing them to perform specific administrative tasks without holding keys to the kingdom.

By naming things clearly and consistently, we enable teams to reason about security, auditors to understand delegation, and architects to design defensible systems. This article defines these categories formally and shows how to implement semi-privileged roles that segregate duties and enforce least privilege.

User categories and trust levels

Active Directory defines user access on a spectrum from unrestricted to highly constrained. Understanding this spectrum is foundational to any security model.

Privileged users hold full administrative power. In Windows, this means membership in Domain Admins or Enterprise Admins; in Unix/Linux, the root account. A privileged account can create users, modify domain policies, reset passwords of other admins, seize control of domain controllers, and export the entire directory database. Privileged accounts are necessary for emergency response and major configuration changes, but using them routinely exposes the entire organization to compromise. If a privileged account is stolen, an attacker gains forest-wide access and can modify audit logs, install backdoors, and disable security controls.

Non-privileged users are the vast majority: office workers, developers, support staff. They have permission to access applications and data relevant to their job, but cannot change system policies, create accounts, modify group memberships, or access sensitive directories. Their capability is intentionally narrow and defensible.

Semi-privileged users hold elevated permissions scoped to specific tasks. A semi-privileged account might manage group membership for a business unit without creating users, reset passwords for a department without accessing tier-0 accounts, or manage DNS records without touching domain controllers. Semi-privileged accounts are bounded: they have more than a non-privileged user but far less than a privileged admin. They are the key to operationalizing Least Privileged Access and Segregation of Duties.

Why semi-privileged accounts matter

The gap between "non-privileged" and "privileged" is vast. A non-privileged user cannot manage any aspect of the directory; a privileged admin can do anything. In practice, most operations do not require full admin power. A help desk staffer needs to reset passwords and modify group membership, but should never create domain admins or export the Active Directory database. A network admin needs to manage DNS and DHCP, but should not modify GPOs that affect security policy. A team lead needs to add team members to resource groups, but should not access financial systems or HR data.

Without semi-privileged accounts, organizations face a dilemma: either grant non-privileged users too much access (violating least privilege), or have them request privileged admins for routine tasks (creating bottlenecks and audit burden). Semi-privileged accounts solve this by allowing delegated admins to perform bounded work without holding keys to the entire system.

Semi-privileged accounts also support the principle of Segregation of Duties. Just as a government separates legislative, executive, and judicial powers, an organization can separate administrative tasks: one team manages users, another manages groups, a third manages resources. By assigning each team a semi-privileged account with only the permissions needed for their function, you prevent any single compromise from propagating to unrelated systems.

Real-world examples of semi-privileged roles

To illustrate, here are four concrete scenarios showing how semi-privileged accounts bridge the gap between non-privileged operators and full administrators.

Help Desk Password Reset Authority: A help desk technician needs to reset user passwords and unlock accounts, but should not have access to sensitive admin groups or ability to modify group policies. A semi-privileged account is created with permissions only to the organizational units (OUs) containing regular user objects. It is granted the "Reset Password" and "Unlock Account" extended rights on those OUs. The account cannot modify group memberships, cannot access admin objects, and all actions are logged via Active Directory auditing. The operator uses this account for legitimate support tickets and is subject to quarterly access reviews.

Resource Group Management: A team lead responsible for a group of file servers needs to create and modify local groups on those servers for access control, but should not have Domain Admin privileges. A semi-privileged account is created and granted ownership of a specific set of servers via group policy. It has "Manage Group Membership" rights on those servers only, enforced through a custom group policy object applied only to those machines. The account cannot modify server settings, cannot access domain-level security, and activity is logged via Windows Event Log aggregation and monitoring.

DNS Administrator Role: The network team needs to manage DNS records in a large zone but not have domain controller or Active Directory admin privileges. A semi-privileged account is created and granted the DNS_Admins built-in group membership. This group has permissions only to manage DNS zones and records; it cannot modify DNS server settings, cannot access Active Directory, and cannot change security policies. All DNS modifications are logged and reviewed monthly.

Organizational Unit Delegation: An IT operations lead responsible for user lifecycle in three regional OUs (Americas, EMEA, APAC) needs to create, modify, and delete user objects within those OUs only. A semi-privileged account is created and granted delegated permissions via Active Directory Delegation Wizard: full control over user objects, computers, and groups within the regional OUs only. The account cannot modify parent OUs, cannot access global security, and all changes are audited. This account is reviewed quarterly to ensure the regional scope is still appropriate.

Pattern Recognition: Each of these roles is bounded by scope (OU, server set, DNS zone), permission (specific extended right or group membership), and auditability (logged and reviewed). The semi-privileged account has enough authority to be useful for its operational charter, but not enough to escalate to domain control or compromise the enterprise.

A semi-privileged role is defined by its function, not by inheriting existing groups like Server Operators or Account Operators. While those built-in groups exist, they grant broad permissions that often exceed what a specific role needs. For example, Account Operators can create users, reset passwords, and manage group membership. If you only need someone to manage group membership, Account Operators is too permissive.

Designing semi-privileged roles

Instead, design each semi-privileged role by answering these questions:

- What is the job function? Be specific. "Help desk" is vague; "reset non-admin user passwords and add users to their department's resource groups" is actionable.

- What AD objects does this role touch? User accounts? Group membership? Specific OUs? DNS records? Document the scope precisely.

- What operations are allowed? Read, modify, create, delete, change password, add to groups? Each permission should be justified by the function.

- What is explicitly forbidden? Cannot touch tier-0 accounts, cannot modify security groups, cannot access domain controller configuration. Spell out the guardrails.

- What is the job function? Be specific. "Help desk" is vague; "reset non-admin user passwords and add users to their department's resource groups" is actionable.

- What AD objects does this role touch? User accounts? Group membership? Specific OUs? DNS records? Document the scope precisely.

- What operations are allowed? Read, modify, create, delete, change password, add to groups? Each permission should be justified by the function.

- What is explicitly forbidden? Cannot touch tier-0 accounts, cannot modify security groups, cannot access domain controller configuration. Spell out the guardrails.

Once you have answered these, create a custom group with a clear, descriptive name: sg-ADmins-PasswordReset-NonAdmins or sg-ADmins-ResourceGroups-SalesOU. Grant only the permissions needed for that specific function. Use Delegation to assign the group permissions on specific OUs or objects, not forest-wide.

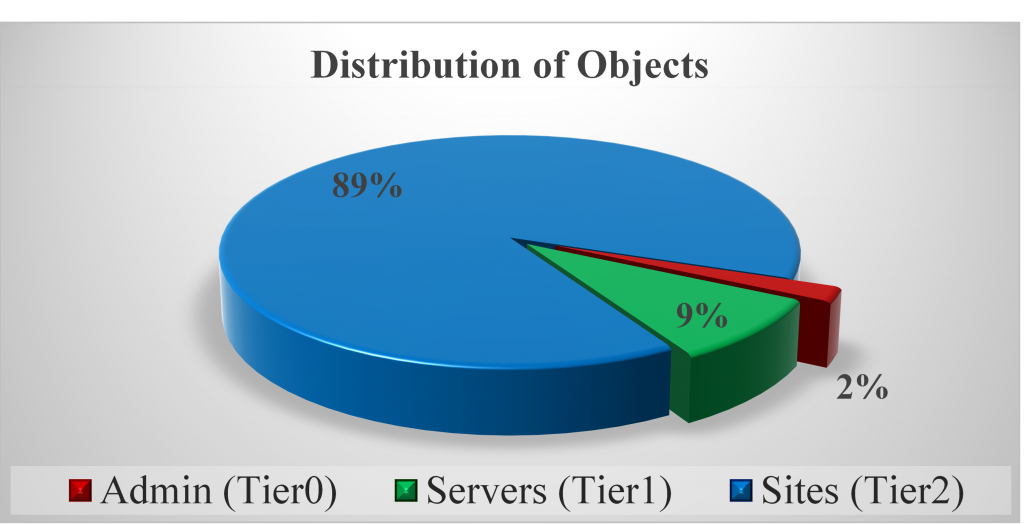

Governance and the 2% rule

As a general rule of thumb, the total number of semi-privileged accounts should not exceed 2% of your overall user and computer objects. This ratio serves as a health metric for your access control model.

Why 2%? Semi-privileged accounts represent exceptions to the non-privileged baseline. If you have 10,000 objects in your directory, ideally no more than 200 should be semi-privileged. A higher percentage suggests that you are:

- Over-delegating authority (too many people with elevated permissions).

- Using semi-privileged accounts as a workaround for poor process design (e.g., "we grant everyone help desk permissions so they can unstick themselves").

- Not consolidating roles effectively (each team has its own semi-privileged accounts when a shared one would suffice).

Monitoring the ratio: Quarterly, audit your semi-privileged account population. Count all accounts that hold any elevated permission (members of built-in administrative groups, custom groups with delegated permissions, or accounts with ACLs granting special rights). Divide by total directory objects. If the ratio creeps above 2%, trigger a review. Ask:

- Can any of these accounts be consolidated?

- Can any be downgraded to non-privileged with improved process (automation, self-service)?

- Are any accounts inactive or unused?

- Do all permissions align with current job functions?

If you consistently exceed 2%, it may indicate that your organization needs to invest in automation, self-service portals, or process redesign to reduce the need for manual elevation.

Bear in mind that the total amount of Semi-Privileged users should not exceed the 2% of the overall objects. Going beyond this percentage might indicate that we have to review our model and semi-privileged account numbers.

Implementation approach

Rolling out semi-privileged roles requires a methodical, phased approach to avoid disruption and ensure proper governance.

Phase 1: Discovery and Audit. Begin with a comprehensive audit of who currently holds elevated permissions. Query Active Directory for members of built-in administrative groups (Domain Admins, Enterprise Admins, Schema Admins, Administrators). Use PowerShell to enumerate custom groups with elevated permissions. Interview operational teams about current privilege requirements. Document every account and its actual function. This inventory becomes your baseline.

Phase 2: Role Definition. For each functional area (help desk, operations, network, DNS, OU management), convene a small team to define the semi-privileged role. Answer the design questions: function, scope, operations, and guardrails. Create a group with a descriptive naming convention (e.g., sg-ADmins-PasswordReset-NonAdmins_Group1). Document the role in a central registry (spreadsheet or wiki) with the operator's name, function, scope, start date, and scheduled review date. Review this registry quarterly.

Phase 3: Testing and Pilot. Before deploying a new semi-privileged role organization-wide, pilot it with a small group. Grant the role to two or three trusted operators for one month. Monitor their activity logs closely. Ask them for feedback on permission gaps or unexpected blocks. Adjust permissions as needed. Once the pilot succeeds, document the lessons learned and roll out to the broader team.

Phase 4: Validation and Ongoing Audit. After deploying a semi-privileged role, audit that operators are using the account correctly. Random spot checks: pull a sample of actions performed by the semi-privileged account (e.g., "reset-pwd" events from the help desk group). Verify that they align with the documented charter. If an operator is using the account for unauthorized purposes (e.g., creating admin accounts when the role only allows password reset), immediately escalate, remove the account, and redefine the role.

Monitoring and auditing semi-privileged accounts

Granting a semi-privileged account is only half the work; monitoring its use is the other half. Without active oversight, semi-privileged accounts can drift from their intended purpose or become vectors for privilege escalation.

Logging: Ensure that all actions performed by semi-privileged accounts are logged. Enable Advanced Audit Policy Configuration on domain controllers to capture detailed events:

- Account Management (event 4722: account enabled, 4726: account deleted, 4728: member added to group, etc.).

- Directory Service Changes (event 5136: object modified, useful for tracking AD changes by semi-privileged accounts).

- Privilege Use (event 4672: special privileges assigned, useful for detecting attempts to escalate).

Aggregation and Review: Forward security event logs from all domain controllers to a central SIEM or logging service (e.g., Microsoft Sentinel, Splunk, Graylog). Create dashboards that show, per semi-privileged account or group:

- Total actions per week or month (for anomaly detection: a sudden surge in activity may indicate abuse or misuse).

- Failed attempts (may indicate a permission gap or an attack).

- After-hours usage (if the account is supposed to be used only during business hours).

- Cross-OU or cross-scope access (if the account is scoped to a specific OU but is accessing other OUs).

Exception Tracking: Semi-privileged accounts often encounter permission denials when operators try to perform edge-case operations. Log these exceptions and investigate at least monthly. Questions to ask: Is this a gap in the role definition? Can it be addressed by expanding permissions slightly? Or is the operator attempting something outside their charter? Tracking exceptions also surfaces opportunities for automation (e.g., "we keep granting manual password resets for managers; let's build a self-service portal").

Quarterly Access Reviews: Every quarter, audit the roster of operators holding semi-privileged accounts. Verify that:

- Operators are still in their designated roles (have people changed jobs without losing their elevated permissions?).

- The role is still needed (are we still doing manual DNS administration, or did we automate it?).

- Permission usage aligns with the documented charter (has the scope drifted?).

- Activity logs show no suspicious patterns (after-hours usage, cross-scope access, repeated denials).

Document the results of each quarterly review. If you find drift or misuse, immediately remove the account and investigate. If you find that a role is no longer needed, retire it and celebrate the opportunity to reduce the attack surface.

Benefits and challenges

Benefits of semi-privileged accounts: When implemented well, semi-privileged accounts enable a least-privilege model that would otherwise require full admin delegation. Help desk staff can reset passwords without Domain Admin membership. Resource owners can manage their own groups without server admin access. Network teams can maintain DNS without touching domain controllers. This segregation of duties reduces the number of powerful accounts in your environment, limits the damage an attacker can inflict if they compromise an operator's credentials, and creates clear audit trails for each operational function. Semi-privileged accounts also reduce dependence on scheduled tasks and service accounts, which are often long-lived and difficult to audit.

Challenges and mitigation: The first challenge is role definition complexity. It is tempting to create vague semi-privileged roles ("IT Staff Admins") to avoid the work of being specific. The mitigation is discipline and documentation. Make role definition a formal process and require sign-off from the team lead and security. The second challenge is tool limitations. Many organizations lack the tooling to delegate fine-grained permissions (e.g., "reset password on this OU but not that OU") and resort to broader permissions as a workaround. The mitigation is to invest in delegation tools or use scripted, automated provisioning that enforces scope. The third challenge is operator discipline. If an operator with semi-privileged access gains even one domain admin account (e.g., via credential theft or social engineering), they can escalate. The mitigation is strong monitoring and rapid response to anomalies. The fourth challenge is exception management. Operators will encounter legitimate tasks that fall outside their scope and will request elevated access for special projects. Without a clear exception process, you will either over-grant permissions (eroding the model) or create so much friction that operators circumvent the system. The mitigation is a documented exception workflow: if an operator needs temporary elevated access, create a justification, get approval, provision a temporary account with an expiration, and audit its use closely.

Related guidance

Semi-privileged accounts are one piece of a larger access control architecture. For deeper context on how they fit into your broader security model, review:

- Tier Model — How to segregate privileged systems and accounts by trust level.

- Least Privileged Access — Strategic framework for minimizing standing privileges.

- Delegation Model — How to define and implement delegated administration roles in Active Directory.

- Role-Based Access Control — Designing and maintaining role hierarchies.

- 0-Admin Model — A specialized tier-0 architecture with minimal standing privileges.

- Enterprise Access Model — End-to-end access control for large, multi-tier environments.

What we can Achieve by using privileged and Semi-Privileged Users

Although we are having more users, these users are controlled and segregated

according to our operational model. All Semi-Privileged users are easily

controlled and audited, and we have the opportunity to implement the "least privileged

access" to them.

By having this kind of users, we are reducing the attack surface of our

environment, as we are not using the powerful privileged accounts for daily

tasks. Remember that this article is only talking about one single brick in the wall,

helping to build it solid and secure!