Introduction

IP addressing is a fundamental aspect of networking that enables devices to communicate with each other over a network. It involves assigning unique numerical labels, known as IP addresses, to each device connected to a network. These addresses serve as identifiers, allowing data packets to be routed accurately between devices.

A communication protocol is a set of implemented regulations to achieve information transfer from one point to another. There are a variety of protocols, but the most widely accepted today is the so-called TCP / IP (Transport Control Protocol / Internet Protocol) better known as IP address.

IP addressing is essential for the proper functioning of networks, including the internet. It allows devices to identify and locate each other, facilitating the exchange of information and enabling various online services and applications.

There are two main versions of IP addressing in use today: IPv4 (Internet Protocol version 4) and IPv6 (Internet Protocol version 6). IPv4 is the most widely used version, but due to the limited number of available addresses, IPv6 was introduced to accommodate the growing number of devices connected to the internet.

IPv4

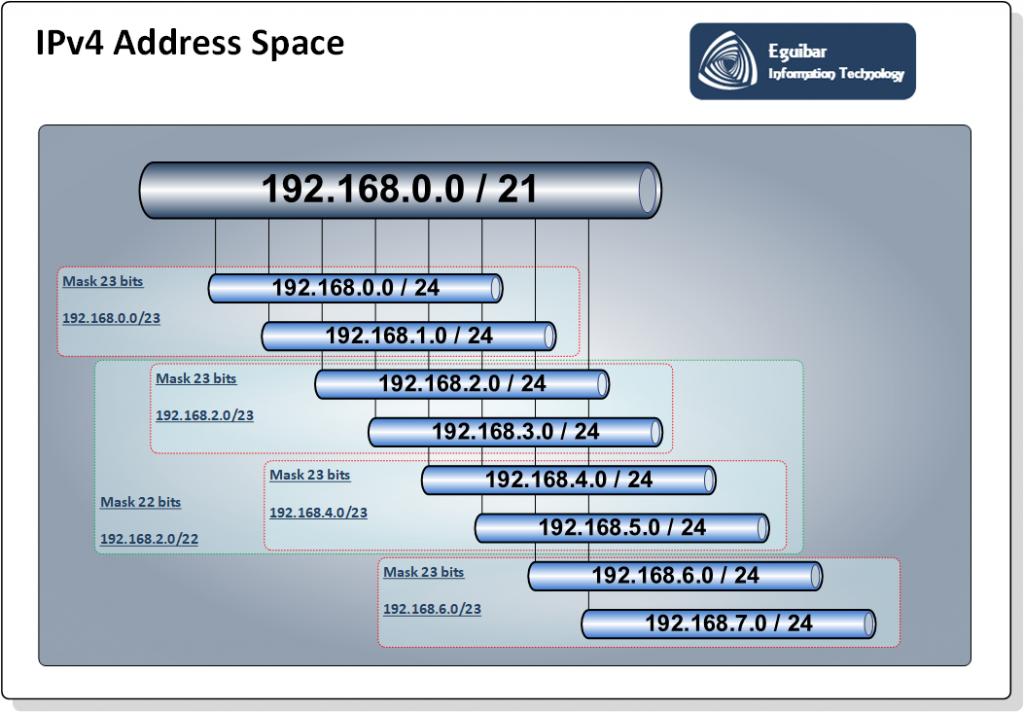

Version 4 of TCP / IP (IPv4) has more than 4 billion addresses (232), which are divided into classes (type A, B, C …). There are Public and Private type. Even when it seems an endless number of IP, are not sufficient for the whole world (web pages, communications devices, mobile devices, virtualization, inefficient use etc.), But fortunately there are different configurations, technologies and services that help us fit address in this dispute.

IPv6

Is the evolution of IP version 4 (232 in other words 4.294.967.296 available addresses). Then, why to change?, this is an easy one, there are no more IPv4 address available. The last assigned block was assigned last February 2011. Then, if we want to continue communicating using IP (which by the way… IS internet) we must adopt this new version, having billions of possible addresses (2128 approximately 3.4×1038).

IPv6 Addressing Fundamentals

Windows Server IPv6 Implementation

This section covers IPv6 addressing fundamentals that apply across all platforms. For detailed Windows Server IPv6 deployment guidance, including Active Directory integration, DHCPv6 configuration, security hardening, and PowerShell automation, see our comprehensive IPv6 Implementation Guide for Windows Server.

IPv6 addresses are 128 bits long (compared to IPv4's 32 bits), providing an address space of approximately 340 undecillion addresses (3.4×1038). This massive address space eliminates the need for Network Address Translation (NAT) and enables end-to-end connectivity for every device.

Unlike IPv4 where address conservation dominated design decisions, IPv6 planning focuses on hierarchy, aggregation, and scalability. The basic configuration integrates the IP address, subnet information, and routing details within the address structure itself, resulting in more efficient routing and improved network performance.

IPv6 Address Structure

An IPv6 address consists of three logical components:

- Global Routing Prefix (first 48 bits): Assigned by your ISP or RIR, identifies your organization on the internet

- Subnet ID (next 16 bits): Allows creation of 65,536 subnets within your allocation

- Interface ID (final 64 bits): Uniquely identifies a device within its subnet

| Component | Bits | Purpose | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Routing Prefix | 48 | Organization identifier | 2001:db8:1234 |

| Subnet ID | 16 | Network segment identifier | 5678 |

| Interface ID | 64 | Host/device identifier | 1a2b:3c4d:5e6f:7890 |

IPv6 Address Notation

IPv6 is hexadecimal, that is we can use numbers from 0 to 9, plus the letters A to F (hexadecimal, or simply hex, is a base 16, or 16 bits, having A=10, B=11, C=12 and so on until F=15). An IPv6 address has 8 groups of 16 hex numbers, separated by a colon “:” having the first address as 0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000 and ending at ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff

Compression Rules: IPv6 addresses can be shortened using two rules:

- Leading Zero Suppression: Omit leading zeros in any hextet (e.g.,

0db8→db8,0001→1) - Zero Compression: Replace consecutive all-zero hextets with

::(can only be used once per address)

Two examples:

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | : | 0db8 | : | af01 | : | b09c | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 027d |

| fd04 | : | eef3 | : | 0000 | : | 0001 | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | a00f | : | 0001 |

These addresses can be simplified. Any block containing zeroes (0000) can be expressed with a single zero (0), as we can see on the second example below, or it can even be more simplified by just having a single zero (0) representing the 3 contiguos blocks. And even more by just having the colons “:” (assuming all omitted blocks are zeroes

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | : | 0db8 | : | af01 | : | b09c | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 027d |

| 2001 | : | db8 | : | af01 | : | b09c | : | 0 | : | 0 | : | 0 | : | 27d |

| 2001 | : | db8 | : | af01 | : | b09c | :: | 027d |

Note: This simplification can be done only once in an address. For example, 2001:0db8:0000:0000:0000:0000:1428:57ab can be simplified as 2001:db8::1428:57ab but not as 2001::1428:57ab

Also, leading zeroes in any block can be omitted, for example 2001:0db8 can be expressed as 2001:db8

So, an address like 2001:0db8:0000:0000:0000:0000:0000:027d can be expressed as 2001:db8::27d

Following the example, the very same address can be expressed as:

2001:0db8:af01:b09c:0000:0000:0000:027d

2001:db8:af01:b09c:0:0:0:027d

2001:db8:af01:b09c::027d

Compression Rule Reminder

The :: notation can only be used once per address to prevent

ambiguity. For example, 2001:db8:0:0:1:0:0:1 can be written as

2001:db8::1:0:0:1 or 2001:db8:0:0:1::1, but not as

2001:db8::1::1.

IPv6 Address Types and Scopes

IPv6 defines several address types, each serving specific networking purposes. Understanding these types is essential for proper network design and security implementation.

| Address Type | Prefix | Scope | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Unicast Address (GUA) | 2000::/3 |

Global | Internet-routable addresses (equivalent to IPv4 public addresses) |

| Unique Local Address (ULA) | fc00::/7 |

Private | Private addresses for internal networks (equivalent to RFC 1918) |

| Link-Local Address | fe80::/10 |

Link-local | Auto-configured on every interface; not routable beyond local segment |

| Loopback | ::1/128 |

Node-local | Equivalent to IPv4 127.0.0.1 |

| Multicast | ff00::/8 |

Various | One-to-many communication (replaces IPv4 broadcast) |

| Unspecified | ::/128 |

N/A | Equivalent to IPv4 0.0.0.0 |

Private vs. Public IPv6 Addresses

Yes, but because of the wide architecture of IPv6, it will not be necessary to use them (or at least meanwhile we live). There are mainly two of them, but there are reserved ranges and exceptions. All the rest of them are called Global Unicast Addresses or GUA.

| Consideration | Global Unicast Addresses (GUA) | Unique Local Addresses (ULA) |

|---|---|---|

| Prefix | 2000::/3 (starts with 2 or 3) |

fc00::/7 (starts with fd) |

| Routability | Globally routable on internet | Private, not routable on public internet |

| Allocation | Assigned by ISP or RIR | Self-assigned (pseudo-random algorithm) |

| Use Case | Production networks, internet-facing services | Internal networks, isolated environments |

| Renumbering Risk | May change if ISP changes | Stable across ISP changes |

| Security | Firewall required for inbound protection | Inherently isolated from internet |

Enterprise Recommendation: Use Global Unicast Addresses (GUA) for production networks rather than ULA addresses. With proper firewall rules, GUA addresses provide end-to-end connectivity without NAT complexity, better support for VPNs and remote access, and avoid the operational burden of managing parallel GUA and ULA addressing schemes. Reserve ULA addresses for isolated lab environments, air-gapped networks, or networks that will never communicate with the internet.

Link-Local Addresses (LA)

This is the equivalent to the auto-configuration APIPA (Automatic Private IP Autoconfiguration) which on version 4 is 169.254.0.0/16. This range has 2 main particularities:

- Is NOT routable. Each configured segment remains within the network, and cannot be routed over public networks and/or interact with other networks.

- Although there are too may addresses, there is a remote possibility to find duplication.

This range includes the loopback address (meaning myself or 127.0.0.1)

::1/128

The designated range is fe80::/10

Key Characteristics:

- Automatically configured on every IPv6-enabled interface

- Required for Neighbor Discovery Protocol (NDP)

- Used for local network communication (router discovery, address resolution)

- Not routable beyond the local link

- Must specify zone ID (interface) when using:

ping fe80::1%12

ULA (Unique Local Addresses)

The difference from LA addresses, is that these addresses can be routed, meanwhile the transmit devices (routers, switches, etc.) are properly configured to accept such range. Explain in it differently, these addresses are not routable through public networks as internet, but they could be on private networks. The range fc00::/7 is equivalent to IPv4 ranges 10, 172.128 y 192.168. On the second example of IPv6 addresses mentioned before, one of this range address is used. A good page which might help us on these addresses is: RFC 4193: Unique Local IPv6 Unicast Addresses (ULA)

IPv6 Address Assignment: SLAAC vs. DHCPv6

IPv6 introduces Stateless Address Autoconfiguration (SLAAC), a mechanism that allows devices to automatically configure IPv6 addresses without requiring a DHCP server. Understanding the differences between SLAAC and DHCPv6 is crucial for enterprise network design.

| Method | Description | Address Tracking | Enterprise Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SLAAC Only | Router Advertisements provide prefix; clients generate Interface ID | None | Workstations, IoT devices |

| Stateless DHCPv6 | SLAAC for address, DHCPv6 for DNS/options | None | Recommended for most clients |

| Stateful DHCPv6 | DHCPv6 provides complete address and configuration | Yes (lease database) | Servers, managed devices |

| Static Assignment | Manually configured addresses | Manual documentation | Infrastructure, critical servers |

Enterprise Recommendation: Use stateful DHCPv6 with statically assigned addresses for servers and infrastructure. For workstations, choose stateless DHCPv6 (SLAAC + DHCPv6 options) or stateful DHCPv6 based on address tracking requirements and operational preferences.

IPv6 Planning Best Practices

Unlike IPv4 where address conservation dominated design decisions, IPv6 address planning focuses on hierarchy, aggregation, and future scalability. The typical enterprise receives a /48 allocation (65,536 /64 subnets).

Hierarchical Address Allocation Example

Consider an organization with a /48 allocation: 2001:db8:1234::/48

| Allocation | Prefix | Purpose | Subnets |

|---|---|---|---|

2001:db8:1234:0000::/52 |

/52 | Datacenter 1 | 4,096 |

2001:db8:1234:1000::/52 |

/52 | Datacenter 2 | 4,096 |

2001:db8:1234:2000::/52 |

/52 | HQ Campus | 4,096 |

2001:db8:1234:3000::/52 |

/52 | Branch Offices | 4,096 |

2001:db8:1234:4000::/52 |

/52 | Cloud Services | 4,096 |

2001:db8:1234:5000::/52 |

/52 | Reserved (future) | 4,096 |

Within each /52 allocation, further subdivide by function, security zone, or VLAN. For example, Datacenter 1 server VLANs:

2001:db8:1234:0010::/64— Domain Controllers (Tier 0)2001:db8:1234:0020::/64— SQL Servers (Tier 1)2001:db8:1234:0030::/64— Application Servers (Tier 1)2001:db8:1234:0040::/64— Web Servers (DMZ)2001:db8:1234:0050::/64— Management Network

IPv6 Subnetting Best Practices

- Always use /64 for end networks: Required for SLAAC and recommended by IETF standards

- Plan hierarchically: Use nibble boundaries (/48, /52, /56, /60) for clean binary divisions

- Document your allocation scheme: Create a visual map of your address hierarchy

- Reserve space for growth: Don't allocate consecutive blocks; leave gaps for expansion

- Use consistent patterns: Apply the same subnet structure across similar sites

IPv6 Security Considerations

IPv6 introduces unique security considerations that require explicit configuration. The vast address space prevents traditional scanning techniques but introduces new attack vectors.

| Threat | Description | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Rogue Router Advertisements | Attackers send malicious RAs to hijack traffic or cause DoS | Deploy RA Guard on switches |

| NDP Exhaustion Attacks | Flood neighbor cache with fake entries causing DoS | Implement NDP rate limiting |

| ICMPv6 Abuse | Attackers use ICMPv6 for reconnaissance or DoS | Filter unnecessary ICMPv6 types at perimeter |

| Transition Mechanism Exploits | 6to4, Teredo, ISATAP create security blind spots | Disable all transition mechanisms in dual-stack |

| Dual-Stack Bypass | IPv6 traffic bypasses IPv4-only security controls | Ensure all security policies cover IPv6 |

Critical Security Reminder

Security policies, monitoring, and incident response procedures must cover both IPv4 and IPv6. Many breaches occur because organizations deploy IPv6 but only monitor IPv4 traffic. Ensure firewalls, IDS/IPS, SIEM systems, and security policies explicitly address IPv6.

Transition from IPv4 to IPv6

The recommended deployment approach for enterprise environments is dual-stack, where devices run both IPv4 and IPv6 simultaneously. This provides the smoothest transition path with minimal disruption.

Deployment Strategy Comparison

| Strategy | Description | Complexity | Recommended |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Stack | Run IPv4 and IPv6 simultaneously | Low | ✅ Yes (preferred) |

| Tunneling (6to4, ISATAP) | Encapsulate IPv6 over IPv4 networks | Medium | ❌ No (legacy) |

| Translation (NAT64/DNS64) | Convert between IPv4 and IPv6 | High | ⚠️ Specific use cases only |

| IPv6-Only | Disable IPv4 entirely | Very High | ❌ Not feasible for most enterprises |

Recommended 5-Phase Deployment:

- Phase 1 - Foundation: Enable IPv6 on core infrastructure (routers, switches, firewalls), train IT staff

- Phase 2 - Internal Services: Deploy IPv6 on DNS, DHCP, Active Directory, and internal services

- Phase 3 - Server Infrastructure: Enable dual-stack on production servers, test application compatibility

- Phase 4 - Client Rollout: Enable IPv6 on workstations in pilot groups, expand gradually

- Phase 5 - Monitoring & Optimization: Implement IPv6 monitoring, tune performance, document operational procedures

IPv6 Subnetting

We already explained that an IPv6 address has 3 parts.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Network Address |

: |

: |

: |

: |

: |

|||||||||

| : | : | : | Subnet | : | : | : | : | |||||||

| : | : | : | : | Device Unique Address | ||||||||||

| 2001 | : | 08db | : | af01 | : | b09c | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 0000 | : | 027d |

2001:db8:af01:b09c::27d

Network Address (Global Routing Prefix)

The first 48 bits of an address, or expressed different, the first 3 blocks of an address (each block is a 16 bits or 4 hex characters). As a rule of thumb, each regional ISP will get a network address, which will be further sub-divided and assigned to other ISP and/or customers.

Example: In 2001:db8:1234:5678::1/64, the global routing prefix is

2001:db8:1234 (first 48 bits).

Subnet Address (Subnet ID)

The following 16 bits, or the 4th hex block. This single detail makes IPv6 way more effective than is ancestor, because communication wise, because the solely address already has the full routing information, source and target, avoiding routing calculations or having to modify the information once sent.

Example: In 2001:db8:1234:5678::1/64, the subnet ID is

5678 (bits 48-63).

This 16-bit subnet field allows for 65,536 subnets within a /48 allocation—far more than most organizations will ever need. Use this space wisely by implementing a hierarchical structure that reflects your network topology and organizational structure.

Interface Identifier (Host Address)

The last 64 bits of the address, or the last 4 blocks. This is the unique device identifier. Some devices can use the MAC address, but a DHCP can dynamically assign it regarding this number.

Example: In 2001:db8:1234:5678::1/64, the interface ID is

::1 (last 64 bits, compressed).

Interface ID Generation Methods:

- EUI-64: Derived from MAC address (automatically configured)

- Privacy Extensions (RFC 4941): Random temporary addresses for client devices

- DHCPv6: Server-assigned addresses

- Manual: Statically configured (recommended for servers)

- Stable Privacy Addresses (RFC 7217): Hash-based stable addresses

Subnet Size Recommendation

Always use /64 prefix length for subnets with hosts. This is required for SLAAC (Stateless Address Autoconfiguration) and is the IETF-recommended standard. Using smaller subnets (/126, /127) is only appropriate for point-to-point links between routers.

IPv6 vs IPv4: Key Differences

| Feature | IPv4 | IPv6 |

|---|---|---|

| Address Length | 32 bits | 128 bits |

| Address Space | ~4.3 billion | ~340 undecillion |

| Address Notation | Dotted decimal (192.168.1.1) | Hexadecimal with colons (2001:db8::1) |

| Header Size | 20-60 bytes (variable) | 40 bytes (fixed) |

| Fragmentation | Routers and hosts | Hosts only |

| Address Configuration | Manual or DHCPv4 | SLAAC, DHCPv6, or manual |

| Broadcast | Yes | No (uses multicast) |

| Checksum | Yes (header checksum) | No (relies on upper layers) |

| IPsec Support | Optional | Mandatory (in original spec) |

| NAT Required | Common (due to shortage) | Not needed |

Related Resources

- IPv6 Implementation Guide for Windows Server — Comprehensive deployment guide with Active Directory integration, security hardening, and PowerShell automation

- Housekeeping Tasks — Includes IPv6-specific maintenance procedures

- Network Architecture — Network design principles and best practices

This guide covers TCP/IP addressing fundamentals for both IPv4 and IPv6. For platform-specific implementation details, see our Windows Server and network operations guides.